‘Freaking hell, just lay out the facts simply at the start,’ says John Safran, writer and celebrated documentary maker. He’s not talking to me so much as to himself. We’re discussing approaches to long form – what he’s learned while writing Murder in Mississippi. And we’re talking on the phone – a fact that will have more resonance for me after our interview than during it. ‘There are ways to simply hook people in. You don’t have to be desperate at the start,’ he says. You don’t have to ‘top load’ the story with everything the reader needs to know. Safran piqued my interest in his writing process at last year's Emerging Writers Festival. He presented days out from submitting his manuscript and flagged the significance of a switch from writing for broadcast to writing a book. Speaking today he says it wasn’t so much of a challenge to make the change (‘I don’t find long form any more difficult,’), as it was to ‘crack the riddle of long form’. It took him a while to work out how he wanted to present his style, his story and his characters.

There are many characters in Murder in Mississippi (which pivots on the case of white-supremacist Richard Barrett and his black killer Vincent McGee) but there are three characters that drive the story forward: Barrett, McGee and Safran. The inclusion of Safran’s own voice is part of his well-honed shtick (‘People want me to do dangerous, idiosyncratic and weird stuff,’ he says). But it isn’t a gag aimed only at pleasing his fans – writing the story from Safran’s point of view enables a logic to the complex unfolding of plot turns and rabbit holes that come out of his research. It frames the narrative and frees him from a chronological retelling – allowing him to reveal aspects to the reader as they were revealed to him. ‘I’m focused on keeping [the story] pure. I try not to be tricky or clever on other levels,’ he says.

This idea of purity also informs Safran’s use of dialogue. ‘You can’t force an audience to think a character is dangerous or funny or real just by asserting it. You have to demonstrate it,’ he says. Understanding dialogue was a part of cracking the long form riddle for Safran. ‘For some reason I thought, Oh you’re not allowed to put a lot of dialogue in ‘cause your readers will think you’ve slacked off and just transcribed dialogue. But then I realised that’s how you bring characters to life.’

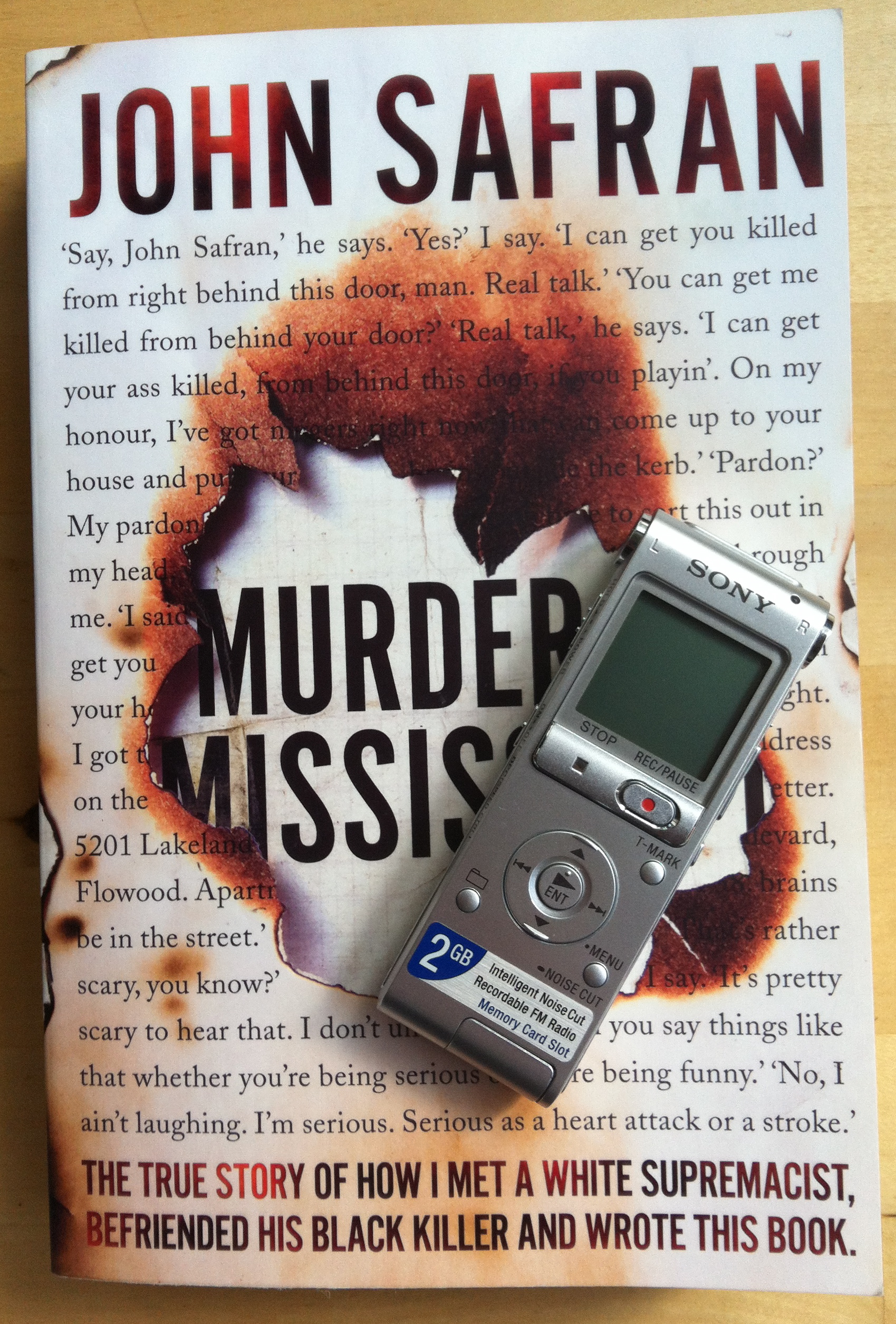

‘One real breakthrough happened when I started blurting into the Dictaphone all the time,’ Safran says. ‘I realised that’s a better way to write things.’ On returning to his apartment in the early days of his US-based research he would just write up notes. ‘But as soon as you start writing you’re already editing things out,’ – a process he found counter productive. ‘[When I’m writing] I somehow feel this obligation that everything has to be watertight and absolutely make sense without any holes. That’s less interesting writing,’ he says. Whereas speaking into the Dictaphone ‘I can say something where I’m leaving stuff out and I’m not quite plugging every hole – but somehow it all makes sense when you transcribe it.’ He regrets not having found the technique sooner – citing aspects of his journey that weren’t included in the story. ‘I was so paranoid that I wasn’t going to make any contact with Vincent and that was going to ruin the book…in retrospect it would have been really cool to have these bits of me really panicking in the book. But I didn’t record them,’ he says. Later he tried to recreate the paranoia and failed. ‘People like my work when it resonates as real.’

Safran recently had a short true crime piece A Town Called Malice published in The Good Weekend Magazine. I asked him if writing true crime was something he might pursue – that he might add to his shtick. ‘I’m interested in crime (at least crime when it’s as extreme as murder) in so much as it brings out the true character in people,’ he says. It’s not the mystery of the crime that catches him but how wider issues (like racism) can be explored through true crime stories. If Safran had gone to Mississippi and told people he was writing about Mississippi and racism then, ‘everything [would be] a bit of a dead end conversation,’ he says. With crime however there’s a reason to talk to people and when they talk, other interesting stories come out. ‘The crime is the perfect spine and the perfect pressure point for me to find out these other things that I’m more interested in,’ Safran says.

Long form was a new challenge for Safran but he wasn’t daunted by it. He read books by other crime and long form writers (William Burrows, Jack Kerouac and Hunter S Thompson among them). He even read a book on verbs. But, he concludes, ‘The only way you can learn is by doing things and the next thing you write is slightly better.’

Safran says that the first draft of his manuscript included a long section about his time in Melbourne (before he went to the US). ‘I spent six months going mad in my flat. I was locked up and I’d be trying to find out all this stuff on the Internet about Richard Barrett,’ he says. Research is crucial. ‘For me at least the trick is to get tons of information,’ he says. But he’s not talking about Internet or book research (which he argues would be near impossible to flesh into a long form piece).

And this is the part of our interview that resonates with me days later when I’m struggling to find an angle for this piece. For the interview I am talking to Safran on the phone and as we talk, different ‘murbles’ (read the book) and ambient sounds travel from his location into my headphones. I wonder – is Safran walking? Sometimes it sounds like he’s on a street somewhere. Sometimes it doesn’t. Perhaps he’s pacing his apartment…? But we’ll never know as this was a telephone interview I did from the comfort of my desk and I can only speculate. The writing process, Safran rightly argues, ‘isn’t hard at all’ once you get out. ‘As soon as you go out there and start with your Dictaphone and your notepad you start just hearing stories,’ he says. ‘And then the story starts writing itself.’