‘It’s a little overcast and there is greenery on the trees – which is lovely,’ Anna Hiatt says of her New York City surrounds. ‘We’ve had the longest winter.’ As she speaks I look through my window onto a suburban Melbourne fence. Autumn leaves fall from vines in the dappled morning sun. Hiatt and I are at the end of a long chat about the future of long form. Hiatt is a freelance journalist (The Washington Post, The New York Times, Reuters and more), long form publisher (The Big Roundtable) and research fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. In February she published a long form piece about the future of long form. The piece, All the Space in the World, provides a high-res snapshot of our current publishing and distribution milieu. Central to this, of course, is the influence of technology.

‘In the beginning was the word, a.k.a. the story,’ she tells her readers. ‘And somewhere along the way … the word lost out to the machine …’ The piece that follows explores aspects of long form publishing via five case studies: the influence of devices and publishing platforms (via Playboy), alternative venues to traditional ones (via Narratively), the appeal of interactivity (via The New York Times’ Snow Fall), amplification (via Longreads and Longform) and changes to reading habits (via Pocket).

Hiatt says that the drive to research the topic stemmed from her work at The Big Round Table where she and her editors (Michael Shapiro and Mike Hoyt) often asked themselves who else was out there and what they were doing. ‘It wasn’t from a business strategy perspective,’ Hiatt explains. ‘We were just curious who the characters were and who the actors were in this field. Basically we wanted to know who our fellow partygoers were.’ Hiatt applied for (and was awarded) a research grant from the Tow Centre. Her initial goal was to try to understand if Snow Fall (published by The New York Times in 2012) was going to be the future of long form.

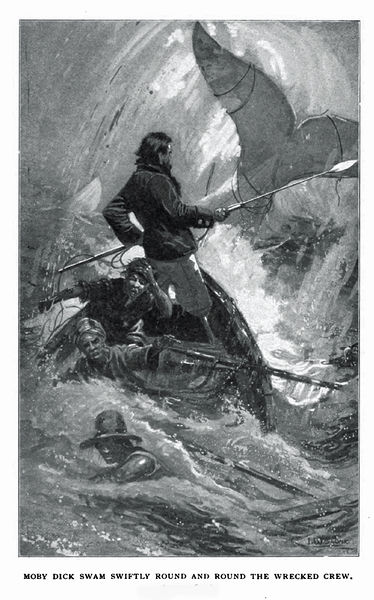

In many circles Snow Fall is seen to be a turning point. The online piece (a story about skiers caught in an avalanche, written by John Branch) includes a number of interactive elements (video, animation, audio) and other graphical enhancements. It was made specifically for online consumption and (as Hiatt notes) was met with much enthusiasm. In fact Jill Abramson (who was Executive Editor of The New York Times when Snow Fall was published) proposed ‘snow falling’ as a new verb – initiating a lexicon to describe this particular type of (online) storytelling. Yet although Hiatt’s research started at Snow Fall, ‘it became pretty clear very quickly that Snow Fall (in the grand scheme of things) was just a blip on the radar.’

‘What was most interesting wasn’t in fact the intricacies of a single piece design,’ she says. ‘It was that we’re at a milestone in storytelling. It just happens to be long form.’

Hiatt’s research piece (All the Space in the World) is published online. Yet it’s a publication of words. There are no videos, no audio and no interactive elements embedded within the writing. She does include an interactive timeline, but unlike Snow Fall, this timeline is provided as a separate chapter to accompany the piece (rather than the reading).

Limited resources were an aspect of this editorial choice (The New York Times had a full-time team working on Snow Fall for months). However Hiatt also admits to valuing words over interactivity. ‘We’ve been doing this for millennia,’ she says. ‘We don’t need things to click to hold people’s attention. If we do, we haven’t told the stories properly.’ Indeed when I ask her what interactive elements she may have included in her own piece (had the resources been available) Hiatt responds by critiquing her writing. ‘I feel like any element [I nominate] would really be me saying that I just should have explained it better [in words].’

I put to it to Hiatt: pieces like Snow Fall – are they really long form or are they part-game or part-website? When does it become a multimedia event rather than just a good piece of writing? ‘I think when it starts to get into the way,’ she says. As a New York local she had both the print and electronic versions of Snow Fall available to her the day it was published. ‘I had an iPad. I was moving my hands all around it and that was really fun,’ she says. But then she put the iPad down and read the article in the paper.

Hiatt’s inclination is one that echoes my own. To me, one of the pleasures of reading long form is being immersed in the story (which, ironically, the multimedia ‘immersive’ elements often counter). If the writing is good I won’t stop for video, audio or other interactive elements. That’s not to say that these new ways of presenting information online are wrong, or have no future. It’s just that they’re different and not really what I consider long form.

‘One of the things that’s so wonderful about radio is that you can sit down and listen and you know exactly the form in which you’re going to get it,’ Hiatt says. ‘One of the things that’s hard for me about going online is that you run across a link – across a page – and you don’t know what you’re going to get. And that (for me) is terrifying. I don’t want to be bombarded.’

As I reflect on my conversation with Hiatt in the following weeks I realise there’s something in our geographical and seasonal contrasts that resonates: something in the conflicting notions of change and consistency. There will always be new growth, blossoms, warm days, orange leaves, bare branches (and even snow fall).

And there will also be stories and words.